Chapter 6 - Public and Private Land Use Controls

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

1) Describe the purpose of having a comprehensive plan for a municipality.

2) Provide at least two examples of requirements found in a local zoning ordinance.

3) Provide at least two requirements found under a State building code.

6.1 Local, State and Federal Ownership of Land

Transcript

While home ownership, and having your own private piece of terra firma to call your own, has been part of the American dream since the first settlers arrived in the early 1600's, the government owns much of the land from sea to shining sea. Government land – properties owned by states, municipalities and the federal government – is used to protect and serve the citizens. In Colonial times in America, land owners thought they had powerful control over what happened on their land, but even then the government retained the right to limit use through regulations about the orientation of buildings, personal use that may cause a nuisance to neighbors and unsafe building practices that impacted public safety and health.

As a real estate professional, you may come across situations that involve the sale and acquisition of public land, and it is important to know some common building and land uses. Let's start at the local level.

Common municipal buildings include: public schools, community centers, libraries, and law enforcement centers for police.

The most common land uses include: city parks, streets, roadways, public boat ramps and city owned recreational places for hiking, biking and sporting events – such as little league ball parks – although some fields are donated by wealthy benefactors.

States have similar holdings as local governments, but on a larger scale. As you can imagine, taming the Wild West during the 19th century was challenging. County courthouses were often the first permanent buildings in Texas counties. It is interesting to note that Texas has more historic courthouses still in use than any other state in the union; two-hundred thirty five, according to the Texas Historical Commission. These iconic buildings are an impressive collection of architectural delights with their ornate copulas and towering brick fortress-like presence.

Along with beautiful courthouses, you'll find modern facilities for both volunteer and paid emergency response teams, maintenance and storage facilities that house road equipment for icing highways during winter months and keeping the public grounds well-groomed. Other government buildings include office complexes for employees that manage state financial affairs, social service agencies and the Capital Complex where legislators make new laws and modify existing regulations. There are also State Parks and stream beds, navigable waterways and public lakes created by dammed rivers. Roadways that begin and end within state boundaries normally fall under State control. Negotiating easements, or right of way contracts, for communications infrastructure and utility access along these roads often involves working with State agencies and private landowners.

The most common buildings and land uses on the federal level include: national parks, military bases, and federal government buildings. Federal government buildings may include structures and land for military training and education, legislative offices, social service centers and some hospitals, like the Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers, outpatient treatment facilities, nursing homes, and post-service training and community outreach programs. The VA currently operates more than 150 medical centers and hundreds of other programs for veterans and active duty personnel.

The reasons for government entities owning land vary. Government ownership usually falls under one of four categories.

The first is serving the public interest. Government buildings allow access to services from health care to financial and legal assistance. Maintaining our national roadways and transportation infrastructure is imperative to serving the public since our food travels on interstates, local highways and by rail. Air cargo ensures rapid mail service. Here's something you may not know. Of the 35,000 United States Post Offices in the United States, 75% are privately owned and leased back to the USPS.

Another reason government agencies purchase land or buildings is to advance urban renewal efforts that revitalize areas of blight or significant decline. The purpose of urban renewal is really two-fold. Declining areas lower the economic potential for all residents. And, severely blighted regions result in reduced tax revenues for local, state and federal entities, which hinders service delivery to the public.

Government agencies also buy land suitable for developing public housing communities, and may buy some existing commercial or private homes that can be modified for public housing.

The fourth category is conservation purposes. The federal government currently owns roughly one-third of the land in the United States. The majority (about 95%) is managed by four agencies – the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service. Government ownership is intended to preserve public lands for public use to enhance quality of life and protect our natural resources.

As a real estate agent or broker, it is essential to understand the role government entities play in the real estate marketplace. Local, state and federal agencies own, lease and manage land and buildings in every community in our nation. It is likely you will have opportunities to negotiate private and public transactions during your career.

Key Terms

6.2 Comprehensive Plans

Transcript

Understanding the impact development has on towns and communities requires careful thought, planning and oversight. A comprehensive plan, also known as a master plan, helps localities establish and enforce rules that dictate how development occurs. The plan establishes a framework for the legal resolution – a document that regulates the use of real property by defining certain limits on land use.

The instrument typically includes restrictions on buildings and other structures, such as the setback, size, height, shape and other features. Using the resolution as a guide, the local planning department tracks development and makes adjustments over time, with public input, as demographics and migratory patterns evolve.

Deciding how development starts, how much building is required to meet public needs and how much is too much is usually overseen by the local planning department and may be altered periodically in response to public proposals and resident needs.

A comprehensive plan covers things such as occupancy limits, parking structures, suburban and rural residential districts and both commercial and private land use. And, planners must consider immediate needs, as well as future use, when creating or modifying the local plan. Let's look at some of the things addressed in a master plan starting with land use.

The public and local leaders may propose designating land for development as residential housing, commercial and industrial activities, mixed-use properties, parks, community facilities and protected habitats for endangered species or migratory fowl. And, within each of these general areas, the plan covers more specific guidance. For example, residential housing considerations may include single-family homes, multifamily structures, land for mobile home parks and planned/or existing assisted living communities. Nursing homes, student dormitories, and on-campus sorority and fraternity houses are considered temporary housing; however, these buildings are also considered in the local comprehensive plan, especially since population demographics are continually changing.

Although many people think of the terms commercial and industrial as interchangeable, there are some key differences when it comes to zoning restrictions and planning activities. Industrial developments are generally areas established for manufacturing. You will typically find factories on the edges of a town, away from residential and commercial land use. Transportation, utilities and financial enterprises do not fall under the industrial umbrella. Commercial land use is any activity, business or investment that operates for profit. Examples of commercial property include everything from a strip mall to a piece of land with an insurance company or hair salon built on it.

This is a good time to mention mixed-use properties. There are a number of reasons that localities decide to zone certain areas as residential and commercial. Large cities with limited land for expansion and a growing need for more housing units may opt to allow retail and residential activity in the same building. Public proposals for change may be driven by an interest in revitalizing a neighborhood, or bringing in new business. Social, economic and cultural factors may all influence modifications to the comprehensive plan in a certain district or locality.

Movement of people and goods also impact the master plan. Net migration, the difference between the number of people moving into an area and the number of people leaving a region, determines how many schools are needed, type and number of roadways necessary to allow the safe, non-congested movement of food and other goods, infrastructure – like water, sewer and other utilities – and recreational areas that improve quality of life for residents. How effectively the planning department evaluates the movement of people and goods is a direct determinant of the characteristics of the community and the quality of life for current and future residents.

Along with commercial and residential land use, planners must consider ways to incorporate community facilities, sustainability goals, public and commercial transportation (such as airports) and protecting scenic views. Community facilities include a broad array of businesses and land use: libraries, public schools, fire and rescue facilities, hospitals and other health care centers, jails, community centers, cultural and religious facilities – churches, mosques and temples – also fall into this category. City owned parks, green spaces, and recreational centers may fall under the community facility umbrella in the master plan as well.

So what about sustainability goals? Because we want to protect the environment and give residents a safe, clean place to live, work, worship and grow, the master plan takes into consideration how development will impact the environment today and for decades in the future. Sustainability goals consider three main factors. Every development decision must evaluate the economic impact to the community, positive and negative impact on the environment and social factors. For example, a new industrial project should serve the residents, while providing a reasonable income to the operators and owners, without generating harmful pollutants. Sustainable goals look at energy consumption and utilizing renewable natural resources for building materials whenever possible. Sustainability goes further than this though.

City planners should ask themselves if proposed development fosters conservation and local energy production, or if using renewable power is possible. They might ask themselves: Will the development promote local food production and reduce food-related waste? Are there any safeguards for precious natural resources including trees and water sources?

Strong, healthy communities thrive in areas where development sustains civic engagement and supports culturally diverse populations. So, while we may think that sustainable goals means “going green,” the comprehensive plan must evaluate ways to balance transportation that increases mobility for the citizens without added more personal cars to the roadways. This includes considering public transportation options like local shuttles, trains and buses to serve new developments.

Public input is vital for every city, district and neighborhood. The comprehensive plan helps ensure that the financial, social and cultural needs of citizens are met. The plan may be modified to reduce building lot sizes, or change commercial only land to a mixed-used zone as such that it will add more housing units, when the population changes. It is critical that planners consider affordability for the elderly, and those who will reach old age in the future. Offering higher densities and small lot sizes when land is limited is one option planners may consider. Another could be to make changes that centralize public transportation and other services to better serve the community and provide access to child care facilities, employment centers, shopping and eating establishments and emergency services. It is all about balancing the needs of today with the needs of the future.

As you can see, the comprehensive plan is a vital instrument. As a real estate professional, you may have opportunities to work with commercial investors, residential housing developers and private buyers looking for a new house or a vacation home. It is imperative that you understand how community development, and specifically the role the master plan, impacts the areas you will serve.

Decided how development will start and progress is not a simple task for the zoning department. When considering natural areas, the planners must consider the historical significance of the land, rare animals and plants that are in the area, and how development will affect future generations. Balancing the needs of the people with the financial goals of commercial developers and future generations is difficult and time consuming, but vital for all stakeholders. While some people think there are too many restrictions on building and both private and business land use, zoning and planning for community expansion is necessary to ensure the health, well-being and financial stability of everyone.

Key Terms

Master Plan

A long-term planning document. It establishes the framework and key elements of a site reflecting a clear vision created and adopted in an open process. It synthesizes civic goals and the public’s aspirations for a project, gives them form and organization, and defines a realistic plan for implementation, including subsequent approvals by public agencies.

6.3 Zoning Ordinances

Transcript

Have you ever walked around a neighborhood and noticed that many of the houses have the same shape?

Perhaps you’ve noticed a consistent number of characteristics such as the front yards being the same depth, or that the houses are all the same height.

If you have, you are most likely experiencing the rules and regulations imposed by the local zoning ordinances being played out.

It is these zoning ordinances that help shape the cities and towns we live in.

So, what are zoning ordinances?

By its definition, zoning is the separation or division of a city or town into districts, the regulation of buildings and structures in such districts in accordance with their construction and the nature and extent of their use, and the dedication of such districts to particular uses designated to serve the general welfare.

In other words, zoning ordinances are a set of laws and regulations that define how a particular property can be used.

If zoning ordinances didn’t exist, property owners would more or less be able to build whatever they liked on their property. Cities and towns would most likely consist of haphazard buildings that were built without a sense of planning. Industrial or high-rise commercial buildings may be built next to residential houses, resulting in non-cohesive neighborhoods and districts.

Zoning ordinances, at their essence, were implemented to protect the health and safety of the population. They commonly regulate what uses are allowed on a particular property, the minimum and maximum size of a property, how densely a property can be developed, and the maximum building size that can be built on a property.

A city or town’s zoning ordinances will be spelled out in the local zoning resolution and zoning maps. These are public documents that can be found through the local planning department and/or department of buildings.

Zoning maps are actual maps of a municipality with the designated zoning districts overlaid on top of the map. A municipality is typically organized into three primary types of zoning districts; residential, commercial, and industrial or manufacturing.

Residential zones are commonly designated with the letter ‘R’ and serve as a zoning district in which residences are permitted. This includes residences ranging from single family homes to large, high-rise rental or condominium towers.

Commercial zones are commonly designated with the letter ‘C’ and serve as a zoning district in which commercial uses are allowed, such as office or retail space.

And, industrial or manufacturing zones are commonly designated with the letter ‘M’ and serve as a zoning district in which manufacturing uses are permitted, such as factories or warehouses.

In addition, each of the primary zoning districts may be broken down into different densities. For example, there may be residential zones that only allow single family homes, while other residential zones only allow large scale apartment buildings.

The zoning maps will graphically show which parts of a municipality can include residential uses, which parts can include commercial uses, and which parts can include industrial uses.

The zoning districts and the permitted densities within each district are typically derived from the municipalities master plan, set forth by the local department of planning. Perhaps the master plan promotes single family communities in a particular area while large scale office buildings are reserved for downtown commercial districts. This will manifest itself in the zoning maps.

The zoning resolution, on the other hand, is a written document that describes, in detail, what can be built on a particular property, based on the zone of that property. The zoning resolution for a small town or village may be very short, perhaps only a few dozen pages long. On the other hand, the zoning resolution for a large city, such as New York City, will most likely be very long and complex.

While the zoning maps will tell you what uses (residential, commercial, and industrial) can be built on a property, the zoning resolution will tell you the “bulk regulations” that must be followed when building a new house or expanding on an existing one.

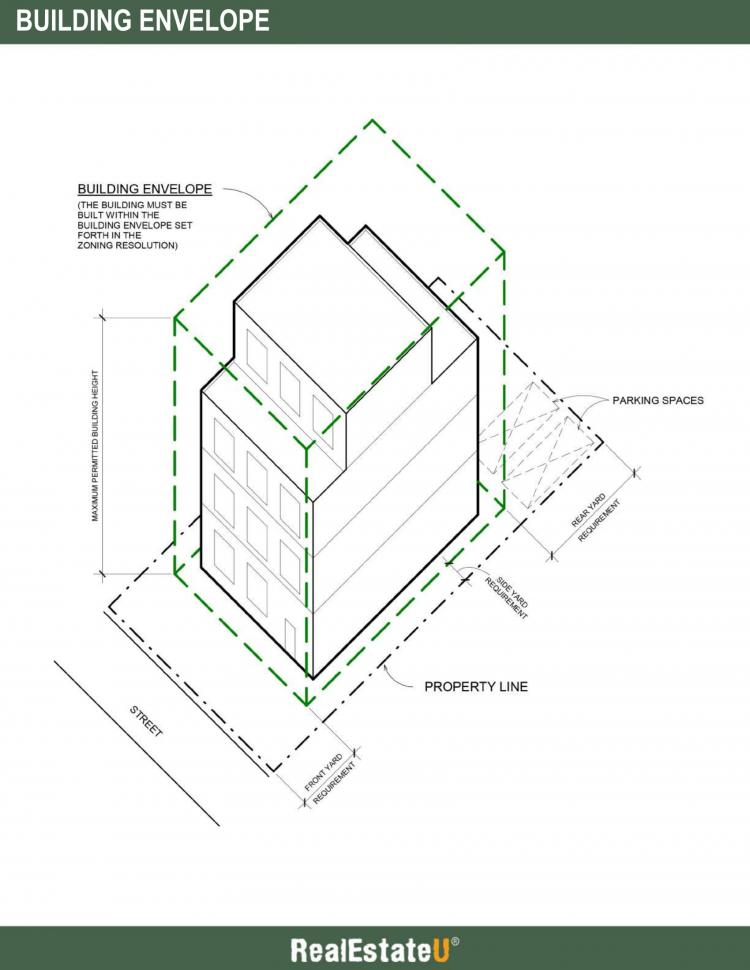

The bulk regulations dictate the allowed building envelope for a structure on a property. The building envelope is the maximum three-dimensional space on a property within which a structure can be built, as permitted by applicable height, setback and yard controls.

In other words, the building envelope set forth in the zoning resolution directly influences the shape of a house or building on a particular property.

When you think of a building envelope, imagine a box set on a table where the building is the box and the table surface is the plot of land where the building is set on. The box has 3 dimensions: height, width and depth, as is the case with any building. The zoning ordinances determine how big the box can be and how much of the table area it is going to occupy or cover.

The building envelope is determined by several fundamental requirements. These include required yard setbacks, the maximum lot coverage or building footprint allowed on a property, the maximum permitted height, and the floor area ratio.

Let’s go over each of these requirements so that you can get a better understanding of how a building envelope is determined.

Each zoning district will have required yard setbacks. This means that the exterior wall of a building cannot be within a certain distance from the property line. In most residential zones, you will have a front yard requirement, side yard requirements and a rear yard requirement. For example, the zoning resolution may dictate that in low density residential zones, all properties must include at least a 20’ front yard, two side yards each measuring at least 10’ wide, and a 30’ rear yard. These yard requirements are typically enacted to allow enough light and air to reach a house. Otherwise, if all houses were built to cover the entire property, our neighborhoods will seem much more crowded and dark.

The yard requirements will give you a perimeter within which a building can be built on the property. Next, you have to factor in the maximum allowed lot coverage. Lot coverage is that portion of a property which, when viewed from above, is covered by a building. The zoning resolution will typically tell you the maximum number of square feet that a building can cover the property. It may be stated as an actual number or a percentage of the property’s area. For example, the lot coverage cannot exceed 50% of the total area of the property.

Next, the zoning resolution will state the maximum height of a building, which again, depends on the zone of the property. Lower density residential zones may cap the maximum building height at 25’ or 30’, while larger scale residential zones may allow a maximum height of 100’ or 120’.

The yard requirements, lot coverage and maximum building height will give you the building envelope, within which the building can be built. The last requirement to check is known as the floor area ratio.

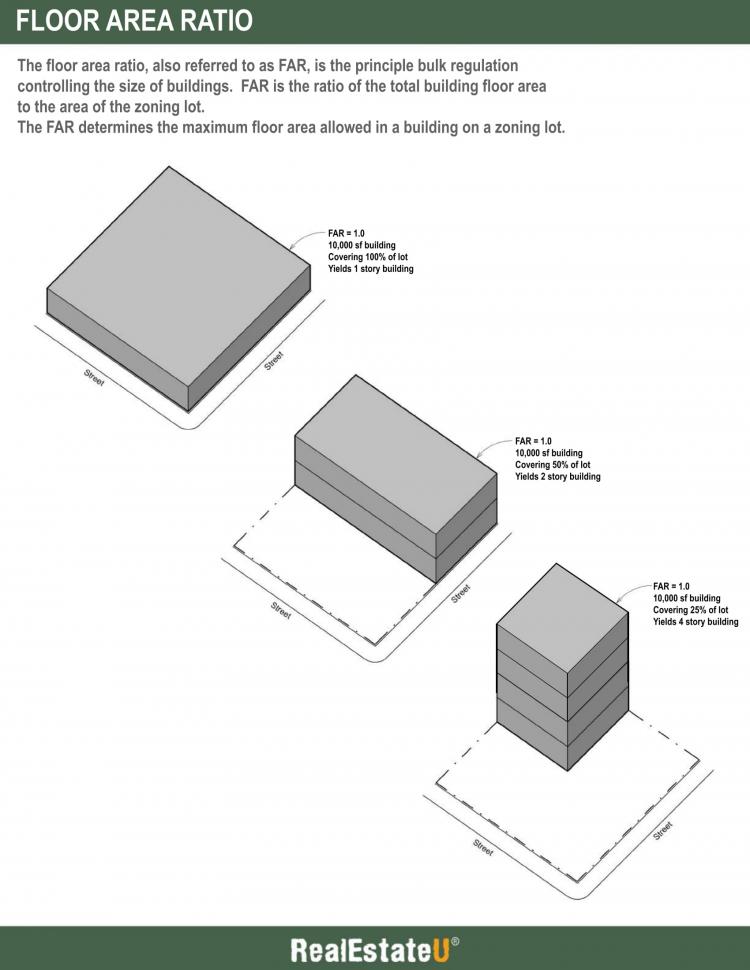

The floor area ratio, as referred to as ‘FAR’, is a formula that determines the maximum allowed ‘buildable’ square footage on a property . It is expressed as a ratio of the total building floor area to the area of the zoning lot. Each zoning district has a FAR which, when multiplied by a property’s area, produces the maximum amount of floor area allowable in a building on the property.

The zoning resolution will typically state the FAR for each zone. For example, a large scale residential zone may have a FAR of 6.0. If a property in this zone measures 10,000 square feet, the total floor area of a building on the property cannot exceed 60,000 square feet (10,000 multiplied by 6). Now, if the zoning resolution allowed 100% lot coverage and didn’t have any required yard setbacks, the building would be 6 stories high. However, nearly all residential zones have such requirements, which would make the building much taller than 6 stories.

So, when you apply these four basic requirements to a property, you can start to see the size and shape of the building take effect.

One last point to note; the zoning resolution will also include requirements with regards to parking. The zoning resolution may demand that a property have a minimum number of parking spaces available in order to reduce the demand for street-side parking in a neighborhood. In addition, a property may be required to have a parking garage in the rear yard with a driveway located in the side yard.

Parking requirements will vary per zoning district, but just remember these requirements have to be considered as well.

Now, when a property fully complies with the zoning resolution, it is said that the property is built “as-of-right”. Most properties you see will be built as-of-right.

When you see a property that is not built as-of-right, it may mean that the owner modified their house without first obtaining approvals and building permits from the local department of buildings. This is illegal and may result in an expensive building violation for the owner.

There are times; however, when the department of buildings will allow an owner to build a structure on their property that does not comply with the zoning ordinances. These are special cases that are granted to owners who are experiencing “hardships” with their property. In these cases, the municipality may grant what is called a variance to the property owner. A variance is the authorization to improve or develop a property in a manner not originally authorized by zoning.

There are two primary types of variances; area variances and use variances

Area variances allow the property owner to build a structure that does not fully comply with the dimensional requirements of the zoning resolution (yard setbacks, height, etc.). For example, if a property is irregularly shaped and cannot fully comply with the required yard setbacks, the local zoning authorities may grant the owner permission to have reduced yard setbacks in order to give the owner the opportunity to build a feasible building on the property.

A use variance, on the other hand, allows the owner to continue using a property in a manner that no longer complies with the most recent zoning resolution. For example, if an existing commercial building now sits in the middle of a residential zone, it will be considered a non-conforming use. The local zoning authorities may grant the owner of the commercial building a use variance, which will allow the owner to continue using the building as such. Often times, the use variance will terminate once the building is significantly modified or torn down. You should never assume that the use variance will extend after the building is sold to a new owner. It is always good practice to verify with the local zoning authorities if the use variance will stay in effect after the property is sold.

Let’s now complete this lesson by discussing how zoning ordinances will play a role in your day-to-day career as a real estate agent.

You will not be asked to conduct a zoning analysis of a property as this is the job of a licensed architect. However, it is good practice to have a general understanding of the zoning ordinances in your market, as this will give you a better idea as to why a particular neighborhood is built the way it is.

It may also allow you to see opportunities that other agents and clients do not see. Perhaps the local planning department recently upzoned a neighborhood, allowing more square footage to be built on a property.

For example, if you know that a neighborhood in your market was recently upzoned from an FAR of 5.0 to 6.0, then the properties in that zone become much more valuable since you can now build 20% more square footage.

There are also times when a municipality would want to revitalize a particular part of the town or city. Over the past few decades, many municipalities have rezoned historically industrial areas, which consisted of abandoned warehouses and factories, into residential and commercial zones. The old warehouses and factories have now been converted into trendy apartments and office spaces.

As a real estate agent, just by following the areas where the local municipality is rezoning and investing public resources, you can spot the ‘path of progress’ in your market. Again, this is valuable information that you can pass on to your buyers and sellers.

Key Terms

Building Envelope

A building envelope is the maximum three-dimensional space on a zoning lot within which a structure can be built, as permitted by applicable height, setback and yard controls. One of the main goals of a zoning analysis is to determine the building envelope. A building envelope is also referred to as the “bulk” of a building.

Floor Area Ratio (FAR)

The floor area ratio, also referred to as FAR, is the principal bulk regulation controlling the size of buildings. FAR is the ratio of total building floor area to the area of the zoning lot. Each zoning district has a FAR control which, when multiplied by the lot area of the zoning lot, produces the maximum amount of floor area allowable in a building on the zoning lot.

Lot Area

The area (in square feet) of a zoning lot.

Lot Coverage

That portion of a zoning lot which, when viewed from above, is covered by a building.

Variance

The authorization to improve or develop a particular property in a manner not authorized by zoning.

Yard Setbacks

A required open area along the property lines of a zoning lot, which must be unobstructed from the lowest level to the sky. Yard setbacks ensure light and air between buildings.

Zoning

The separation or division of a city or town into districts, the regulation of buildings and structures in such districts in accordance with their construction and the nature and extent of their use, and the dedication of such districts to particular uses designated to serve the general welfare.

Zoning District

A mapped residential, commercial, or manufacturing district with similar use, bulk and density regulations.

Zoning Maps

Maps that indicate the location and boundaries of zoning districts within a municipality.

Zoning Ordinance

A statement setting forth the type of use permitted under each zoning classification and specific requirements for compliance.

6.3a Building Envelope Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

6.3b Floor Area Ratio Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

6.4 Subdivision Regulations

Transcript

This lesson will talk about subdivisions and the regulations in place that ensure development follows a certain set of guidelines to protect and promote the general welfare, safety and health of a community and its residents. Today, every state has standards for subdivision developments. Before we talk about how regulations ensure an orderly development, let's talk about what a subdivision is. Usually, a developer or real estate investor group buys a large tract of land suitable for dividing into smaller properties to build individual houses on.

But, it isn't as simple as just clearing a piece of land and erecting homes. Local ordinances dictate the development of subdivisions. Developers must first create a written diagram, sometimes called a subdivision plat that details the land division and proposed property improvements. Depending on whether the land is in an incorporated or an unincorporated area, a county commissioner’s court, zoning office or other government entity has to approve the plan. Proposed developments must follow standards established by the area comprehensive plan, although master plans may be modified to include approved subdivision plats and allow recording.

To understand why subdivision regulations have been adopted across the country, let's look at how a subdivision is created. The developer starts by ordering a survey of the land. The survey is a foundation for recreating a plat map. Remember, the plat must be approved by the local department of building before any improvement and construction can be started. Subdivision regulations govern the land development process through each phase. For example, every residential lot must have safe, efficient access. So, developers must plan for roadways, utility infrastructure and drainage systems to keep the area safe after heavy rains. These improvements must be carefully planned to ensure adequate water is available and that the local government won't have to bear unnecessary financial burdens constructing or maintaining safe living conditions, for current or future residents. Local ordinances may require the developer to assume all cost of roadway repair and maintenance for several years to make sure the quality of the materials and workmanship are adequate to protect the local government from financial risks. The developer must also consider waste removal and wastewater treatment. The subdivision plat details the rights-of-way and easements necessary to provide these services via streets, alleys and other types of access. The plat also establishes a means of transferring ownership to the first residents in an area as well as future buyers.

The developer is typically responsible for overseeing and assuming the financial burden of constructing all streets, roadways, alleys, sidewalks, public squares and designating community green spaces, such as parks, nature trails and other non-residential lots facing or adjacent to these improvements. Prior to building any homes, the subdivision developers usually connect each lot to existing local utilities, water and sewage systems.

To recap what we have covered so far on creating a subdivision plat. The plat provides a visual layout of the proposed subdivision, and individual tracts within the subdivision. It also identifies the total acreage for development, and the approximate size of each residential tract, as well as areas dedicated for public use, such as sidewalks, alleys and green spaces. Plus, the map shows the location of both private and public roadways in proximity to the subdivision.

Developers may spend months or even years preparing a large tract of land for subdividing. For example, deciding where to put roadways is only the first step. You must also consider what type of roadway will best serve the community based on anticipated traffic patterns within the subdivision, and whether arterial roadways – main highways that provide access throughout a city or county – will be impacted by the new development. Most governing agencies require all streets within multi-family, commercial and single-family subdivisions, and any roads that will intersect with existing county roads be paved. The width of the roadway is determined by the type and placement within a subdivision. Variations in width are often impacted by current utility rights-of-way and drainage requirements. However, developers must consider whether shoulders should allow for widening roadways in the future if traffic patterns change or surrounding area development creates a larger volume. Subdivision regulations even dictate what type of materials may be used to build streets and roads.

While we are talking about roads, this is a good time to mention a few other things governed by subdivision regulations. Think about all the things you see as you drive through a subdivision. Ornamental, also known as decorative, landscaping and irrigation of public green spaces are addressed in subdivision regulations. Most counties don't allow any landscaping that may interfere with line-of-sight when traveling roadways. So, subdivision entrances must be designed to provide a clear view of traffic entering and exiting a community. Developers are also responsible for creating safe roads, so traffic signs and guard posts are covered along with street name signs, reflectors and speed bumps. And, each of these items has specific guidelines for size, shape and color, in most counties. Street signs may have a minimum and maximum height, as well as dictates about whether or not letters should be upper or lower case. And, every subdivision must install approved traffic stop signs, and information signs, such as the Deaf Child signs seen in an area where children with hearing deficiencies live.

Driveways, which may be built before or after houses are erected, must not block drainage systems. Engineers typically provide advice about culvert placement, size and type to ensure all driveways are “user-friendly” and safe. Subdivision regulations provide information about the minimum length and width of paved driveways and how they connect with paved roads to ensure that no part of the drive is built on a utility easement other right-of-way. Even mailbox placement and design may be governed by subdivision regulations, state transportation standards and other restrictions.

Not every subdivision regulation is imposed by municipalities or government agencies. For example, developers create restrictive covenants for a variety of reasons. A developer could plan a community that will become subject to Homeowner Association bylaws and rules. Or, lots may be sold with deed restrictions that establish how the property can be used while prohibiting certain commercial activity. Easement can provide access, or restrict improvements to preserve green spaces and wildlife habits. Developer imposed restrictions typically include aesthetic components that enhance or beautify the community while maintaining a common architectural style. House sizes, setback lines and certain landscaping rules help developers shape the feel, tone and appearance of the subdivision.

Every subdivision develops a unique rhythm and culture. When reviewing a subdivision plan, the local authority evaluates the document for some essential elements. Will the subdivision support the economic, social and physical needs of current and future residents? Does the municipality have the resources – fire and emergency services, medical centers, water and energy reserves, and finances – to support a new subdivision? A well-designed subdivision plan is science-based. Developers use demography – the study of populations – to predict how births, deaths, migration and aging will impact housing needs in the near and long term. Oversight commissions and zoning officials want to see evidence in the plan that developers have considered population dynamics.

And, then there are the other regulations that directly and indirectly influence building the houses once the lots and easements have been established. If the project managers anticipate that future owners may use Federal Housing Authority (FHA) financing, the land and improvements must meet the agency guidelines and regulations. And, every new development must comply with local Zoning Ordinances, which may include lot size, building footprint, minimum parking space per capita and building height requirements.

As you can see, developers spend more time planning a subdivision than actually building the homes on individual lots. According to the 2012 Census Bureau Survey of Construction, on average it takes about five to eight months to build a single-family home ready for occupancy, after you receive the building permit. Getting approval for subdividing a large tract in some municipalities could take years. This tells us that dividing a large piece of land into individual lots for sale, development or transfer is not a speedy process.

Subdivision regulations ensure future owners, surrounding neighborhoods and the local municipality all benefit from the expansion. Developers may have the initial vision, but it takes dozens, if not hundreds, of people to go from a blank sheet of drafting paper to an approved, recorded plat. Subdivision regulations play a vital role in shaping the process for a community that will blossom from concept to completion.

Key Terms

Subdivision Regulations

The control of the division of a tract of land into individual lots by requiring development according to specific standards and procedures adopted by local ordinances.

6.5 Building Codes

Transcript

Building codes established and enforced in municipalities today regulate the construction of buildings and other structures to protect the health, safety and welfare of the general public. Although some major cities in the United States still have their own building codes, most municipalities adopt a State code as the foundation for local building control, and modify the regulations through amendments based on their unique goals and resources. Some states build on the International Building Code (IBC), which serves as a national model in the United States.

Building codes evolve over time through amendments and modifications.

It is interesting to note that building codes in the US did not start out as government regulations designed to protect the public. Around the turn of the 20th century, huge conflagrations in San Francisco and Baltimore, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, compelled insurance companies to explore ways to manage risk more effectively. Working with the National Board of Fire Underwriters (NBFU), the industry developed a survey that considered every aspect of a municipality from topography and local weather to civic affairs and roadways. Using this survey, insurance companies established guidelines for building codes that addressed doors, shutters and building materials, as well as fire department equipment and fire house locations. Their goal was to encourage municipalities who wished to get the most favorable rates that they would adopt these guides. Early building codes were driven by financial motives, and developed to protect property, not people.

Let's talk about what is covered under a building code.

Remember those exhaustive insurance company surveys mentioned a minute ago? If you look at what is regulated by building codes today, you can see fire protection still plays a significant role in shaping the municipal policy. However, in recent years there has been a push to implement sustainability guidelines that protect the environment, curb energy consumption and reduce our nation's carbon footprint.

Here is a brief snapshot of some of the various components covered in standard building control policies.

Construction Type: A primary focus in the code is establishing building construction rules and guidelines. The type of building materials used often determines how the building may be used, the size, placement and number of fire exits in a building and the type of fire protection required. Most buildings are erected with a wood, concrete or steel frame.

Other Building Materials and Supplies: Municipal ordinances and building codes also cover things like paint, types of pipe and electric wiring. At times, a variety of agencies may have overlapping regulations that directly and indirectly govern building construction and rehabilitation. Consider lead abatement. Multiple agencies contribute laws and statutes regarding the removal, disposable and use of lead-based paint. Since 1960, New York City has banned the use of lead-based paint in almost all residential dwellings. There are a few exceptions. Condominium owners are not required to remediate homes with existing lead-paint, as long as they occupy the home. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues rules about disposal and removal during rehabilitation. And, many states like California, have enacted Health and Safety Codes and Housing Law, that governs contractor licensure, disclosure rules and guidelines that established to prevent childhood exposure. Not all of the rules fall under the umbrella of building code enforcement, but it is important to recognize few code amendments are developed without considering whether new regulations will intersect with existing standards.

Occupancy Type: Occupancy is based the structural material and intended use. For example, the code only allows single-family residences to be built using wood frame – sometimes called stick-built – construction. Commercial buildings, multi-family homes, office and retail space and industrial/manufacturing structures must be built using concrete or steel frames.

Building code establishes a maximum of permitted occupants per floor and per use. There are specific formulas for calculating occupancy rates based on normal activity in a building, or on a specific floor. As an example, IBC code recommends 15 square feet of floor space for each occupant in an area without concentrated seating. That means a restaurant having 1,000 square feet furnished with well-spaced tables and chairs could accommodate 66 patrons. A dance club on the other hand, with more concentrated use of chairs, only has to have 7 square feet of floor space per occupant. So the same 1,000 square feet could safely accommodate a maximum occupancy of 142 customers.

Since building occupancy is determined by floor area and height (i.e. stories), let's discuss some limitations and flexibility within the code. Wood frame structures are limited to two stories and smaller floor area than concrete or steel structures, with a few exceptions. You will never see a wood frame skyscraper. Some building codes don't limit the height or floor area for steel and concrete frame construction.

Not all wood structures follow the same regulations, though. Consider log home construction, which is governed by ICC 400-2012. Log construction has a unique set of requirements, in addition to the standards that cover plumbing, electrical, foundation and mechanical codes. The standards establish metrics for lumber grade, sustainability, fire resistance, potential for shifting, energy-conservation, and wall protection via specific roof designs that channel water away from the building envelope. Today's log homes may be small cabins or massive three-level homes with 7,000 or 8,000 square feet, depending on the location and local building code considerations.

Exit and entrance requirements depend on the type of construction and use as well. The number and location of egress points are typically determined per floor. Floors with more occupants, such as hotels or apartments, require more exits than single family homes and small business locations. In multi-story buildings, an exit is generally a fire-rated stair leading to the lowest, or ground level, floor. The municipal building code also describes the maximum travel distance to an exit. This distance is calculated by measuring the distance from the most remote point on a floor from a fire exit or stair.

Standards determine the width of a fire stair based on projected occupancy and building use. Let's take a look at a function hall to better understand how hallway, door and stair width impacts safety during a fire.

The IBC recommends stair exits have at least 0.3 inches of doorway per person to allow safe egress. Traditional doorways require 0.2 inches per occupant. A meeting room with a 2,000 person maximum occupancy on the ground floor without stairs needs 400 inches of doorway, or 12 exit doors.

There must be at least one operable window, door or other device in every room used for sleeping quarters that allows safe entrance and egress during an emergency. Sizes mandates vary by region. The International Residential Code (IRC) has extensive recommendations for health and fire safety, including:

- The egress window must have a minimum glass area that measures at least 8% of the total square footage of the room (or rooms) it services to allow sufficient natural light to flow through the window

- The minimum opening for egress windows must be 20” by 24” (height X width)

- In order to provide adequate natural ventilation, an egress window must have an opening that measures at least 4% of the square footage of the room, or rooms, served

Fire protection as a means to preventing loss of life has been a major driving force behind building code enforcement since 1947, when President Truman order a national conference on fire safety and prevention after two significant hotel fires claimed dozens of lives. Forty-one percent of guests staying at the Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, lost their lives when fire broke out on December 7, 1946. Just a few months earlier, 61 people lost their lives in the La Salle Hotel fire in Chicago. Both tragedies could have been avoided, or perhaps fewer people would have died, if the stair designs had provided more protection from the spread of fire, such as installing doors in the stairwell and making sure there was adequate egress based on occupancy numbers.

Building code standards don't just address the primary construction type and intended use, though. Like log home guidelines that require specific fire resistant applications, codes determine the minimum fire protection standards for each building type. Fire protection measures may include:

- Applying spray-on fire-proofing material to steel members in steel frame structures that provides at least a 2-hour protection window

- Installing sprinkler systems and/or fire suppression systems in commercial, industrial, retail and multi-family buildings

- Special guidelines for mixed-use buildings may require a minimum protection wall between residential and commercial spaces. For example, if a mixed-use building houses a bakery, restaurant, or other retail space on the first floor and housing on upper floors, the code may require a 2-hour separation – or enhance fire wall between the floors

- Installing gypsum separation walls between adjoining townhouses or condos. Gypsum partitions provide 2-hour fire protection and are constructed with steel studs and tracks and gypsum liner panels joined by aluminum clips. These types of walls are typically seen in buildings with one to four stories.

Occupancy codes also address accessibility for disabled persons. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) details design requirements for most public buildings and residential rental buildings. The standards establish guidelines for door widths, corridor widths, ramp requirements, parking structures and other features. If State or local code conflicts with ADA standards, the more stringent regulations will typically be adopted and enforced.

Here are a handful of ADA guidelines that inform building code development.

- Door width under ADA standards must measure between 32 and 48 inches; however many municipalities and some states, recommend a minimum of 36 inches to accommodate larger wheelchairs and walkers.

- Ramp design is complex and varies depending on whether the ramp is built to accommodate public access or as part of a handicap accessible resident. ADA standards require one linear foot of ramp for every inch of rise. Builders use a 1:12 slope ratio to achieve that benchmark. Other regulations govern landing size, curbs, sidewalls, handrails and width, depending on whether the ramp is an external or interior improvement. Compliance with ADA standards requires a 5' X 5' turn/landing platform; however, California code is more stringent, requiring a six foot minimum in the direction of travel. Guardrails in most states must be between 34 inches and 39 inches, and must be installed on both sides of the ramp.

- Corridor/Hallway width varies significantly depending on the environment. While the standard is 36 inches, some exceptions are made to allow certain hallway sections to accommodate architectural features. Some codes allow reduced width as long as the narrow spaces are limited in length to a short distance and there are at least 48 inches of length between the reduced widths to navigate the route safely.

- Standards for protruding objects in circulation paths, such as water fountains in public buildings. Circulation paths are more than just hallways. They also include walks, courtyards, platform lifts, stairways, ramps and even connecting corridors between rooms. To allow people with visual and mobility challenges, designers must consider wheelchair bound persons as well as people who use a blind-cane or walker. There are both vertical and horizontal standards. For example, cane detection areas are below 27 inches. Anything protruding from the wall must be positioned between 27 inches and 80 inches above the floor, and extend no more than 4 inches into a circulation path. Handicap rails are the exception, and in most cases may extend up to 4 ½ inches into the path. There are some exceptions for different types of protrusions. Objects installed on poles and pylons may extend up to 12 inches into the pathway or corridor.

There are many building code sections, but we have covered the most common here. Now let's discuss the Certificate of Occupancy. Once all required inspections have been completed and successfully passed, a local governing body issues a Certificate of Occupancy, often referred to as the final CO. This document certifies a house (or other building) is safe for habitation or commercial use. The CO demonstrates that the completed project significantly follows the design set forth in the original application for a building permit.

While each local authority may require a different set of inspections before issuing the CO, most require a plumbing inspection, fire marshal review, electrical inspection and, when appropriate a health department certificate and ADA compliance survey for public buildings and rental properties that will serve disables persons. Special inspections may be required if a building has one or more elevators, utilizes a dedicated water system and for mechanical features, such as heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems installed.

And now some final thoughts about building codes and real estate markets.

As a real estate agent, you may work with developers, builders and individual homeowners. Understanding how building codes impact land and building investments is essential to serving these diverse groups with different financial goals.

Keep in mind that geographic location, community culture, global initiatives and private industry all shape regional codes, and may trigger amendments. Tragic events, such as the fires that prompted President Truman to lead the effort to improve fire prevention strategies, may stimulate modification to local codes. Innovation and activism may also drive change, as we have seen in recent years with the development of sustainable building materials and alternative energy options like solar and wind find their way into building standards from Bangor, Maine to San Francisco, California.

Remember that local code enforcement doesn't just apply to new construction homes. According to 101.4.2 of the Florida State Building Code, statutes govern “…the construction, erection, alteration, modification, repair, equipment, use and occupancy, location, maintenance, removal and demolition of every public and private building [and] structure.” Florida is a state that has different code regulations for every county.

For example, building codes in communities along the Florida coast may include standards for elevating homes to protect assets from tidal surges and weather related beach erosion. Broward and Miami-Dade counties require additional design features that protect against wind-borne debris from high-velocity hurricanes. State codes also include mandates to protect and preserve coastal barrier dunes from construction activity that could destabilize the beach-dune ecosystem.

In parts of Texas, State building code may include special requirements to strengthen fire-proofing standards to protect people and assets in rural communities at risk for wildfires or enhance design to reduce damage from tornadoes. Safety experts encouraged the State to update existing codes after a devastating tornado plowed through Dallas in 2016, urging lawmakers to seriously consider adopting state-wide standards that reduce risks during inclement weather events. Among the suggestions were changes that force or encourage improvements to:

- Minimize damage by reinforcing the roof system

- Incorporate stronger building envelope elements, such as windows and doors designed to withstand high winds and flying debris

- Form a continuous load path that runs from the roof to the foundation

While not required for this course, you might spend a few minutes thinking about the community where you live. Are there special environmental factors that could influence changes in the local building codes? Have recent academic or scientific research identified threats to the general population – like lead-based paint? Does your climate include severe weather events like blizzards, hurricanes, earthquakes or prolonged periods of excessive heat? These are the types of questions city leaders must carefully consider to ensure the health, safety and welfare of the citizenry.

Key Terms

Building Code

A systematic regulation of construction of buildings within a municipality established by ordinance or law.

Certificate of Occupancy

A document issued by a local government agency after satisfactory inspection of a structure authorizing that the structure can be occupied.

6.6 Environmental Protection Legislation

Transcript

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created in 1970 during the Nixon administration to deal with emerging environmental problems caused by excessive pollution from industrialization, transportation methods and unchecked hazardous chemical applications. The original goal was to stem the escalating negative impact on human health and the natural environment. By creating an agency that encompasses federal research, environmental monitoring, standard rules and regulations and enforcement under one umbrella, Congress hoped to encourage – and force when necessary – individuals and businesses to take a more mindful approach to how we balance growth and progress with responsible stewardship.

Some of the EPA laws set benchmarks to protect water resources, while others establish rules banning the use of certain chemical compounds for commercial use that could cause long-term or permanent damage to soil or irreversible health problems for humans and animals.

Some of the laws on the books today restrict the type of building materials and what type of buildings or structures can be built in certain areas.

Let's explore a few rules that directly impact real estate development and sales activities.

First, we'll talk about the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability ACT (CERCLA). Also known as the Superfund, CERCLA became law in 1980. Many of the EPA regulations seek to encourage the development and use of benign chemicals to control weeds and insects, disinfection our living spaces and treat building materials to enhance strength and durability, the Act, provides funding to remediate hazardous conditions. CERCLA established a fund to clean up uncontrolled hazardous waste at sites identified by the EPA as priorities in need of immediate attention. Special taxes collected from the oil and gas industry funneled $1.6 billion into the fund in the first six years after ratification.

While CERCLA's primary objective was to immediately remove any threat, the rules also included guidelines to minimize and prevent pollution threats and stabilize the environment by targeting sites with listed hazardous materials and any known contaminants, with the exception of oil and gas which fall under other federal standards.

The EPA standards attempt to reinforce personal accountability. And, the agency has authority to sanction responsible parties who fail to remediate contamination problems. For example, people who transport substances on the National Priorities List and both past and present site owners may face financial and other consequences if they fail to voluntarily clean up the mess. If a responsible party fails to take action, the EPA is authorized to initiate removal actions using Superfund resources.

Some regulations overlap with CERCLA; however before we go forward with that discussion, let's back up just a minute. Did you catch that part about personal responsibility that says “current and past owners” may have liability under EPA standards? As a real estate broker or agent, you have a responsibility to help prospective buyers research the history of a building site and both occupied and unoccupied industrial/manufacturing facilities. Lawful and unlawful commercial activity prior to 1970 may have allowed now-banned chemicals to be stored underground or dumped as waste water near or in rivers and streams – polluting the water supply directly or indirectly through soil absorption.

Environmental protection legislation doesn't just govern irresponsible use and disposal of man-made chemical solutions. Did you know that radon, a naturally occurring gas, is the second leading cause of cancer in our country? It appears in ground water and air as a bi-product during the breakdown of uranium. Some building materials such as exotic granites, cement, Basaltic rock, pumice and Gypsum waste also emit radon.

The EPA updated their radon exposure prevention guidelines in 2013 to recommend everyone who purchases a home test for radon as soon as possible after occupancy. Additionally, the agency suggests people building new homes ask their contractor to utilize radon-resistant materials and sub-foundation construction techniques to mitigate radon transfer from the air, private wells and surrounding soil.

Now let's talk about the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) of 1986. The EPA spent the first six years learning on the job, so to speak. SARA reinforced the initial objectives and made changes based on knowledge gained. For example, SARA strengthened the focus on human health problems associated with hazardous waste sites and encouraged the public to get involved with the decision-making processes behind initiating best-practices for cleaning up “dirty sites.” The Act provided new enforcement authority, while giving states more involvement in standards development. SARA also requires that all remedies and legislation consider existing State and Federal environmental rules and laws. Perhaps the most significant change was an increase in funding that brought the total Superfund trust to $8.5 billion.

As mentioned earlier, some EPA legislation overlaps with other regulations. As an example, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) provides protocol and rules for underground storage tanks containing petroleum-based products, non-hazardous waste, medical waste and toxic waste; however, CERCLA provides guidelines for the types of controlled waste. The two legislative initiatives enjoy shared jurisdiction. The Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and other environmental rules often intersect with independent EPA regulations, as well as both state and federal laws.

Earlier, we mentioned radon gas, which is found in water sources and private wells in almost every region of the United States. Ideally, all commercial and residential property water supplies would be tested for radon before transferring ownership. This doesn't always happen though, so the EPA has numerous regulations enacted to protect public health and wellness. One example is the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), approved by Congress in 1974, which established safety standards for public drinking water. The law has seen two amendments, one in 1986 and another in 1996. While SDWA rules cover water sources, including lakes, rivers, springs, streams and underground wells, the EPA does not monitor or otherwise regulate private or commercial wells that serve fewer than 25 people. The standards aim to control, eliminate or mitigate both man-made and naturally occurring contaminants. There is an ongoing partnership between the EPA, state regulators and a variety of water systems to ensure health-based standards are upheld across the United States.

Recognizing the vast number of threats to safe drinking water for humans and animals, SDWA initially focused on monitoring and improve water quality at the tap – or faucet. However, the 1996 amendment addressed threats from improper chemical disposal, pesticides and waste injected underground with a broader approach. The modifications enhanced existing law by creating an overarching policy to ensure safer water from the source to the tap. This meant that new guidelines laid the foundation for eliminating barriers to:

- Modernizing water systems

- Providing advanced operator training

- Access funding opportunities

- Expanding public information campaigns

- And, implementing innovative source water treatments

This fundamental change made it more efficient to address environmental contaminants from animal waste, chemical disposal, underground substance storage leaks, human threats and other potential and known hazards to a clean water supply.

Two other important EPA regulations are the Clean Water Act (CWA) and the Clean Air Act (CAA). Some people confuse the SDWA with the CWA. While SDWA governs clean water from the original water source to a consumable beverage, CWA primarily regulates source water – think bodies of water like the Great Lakes, rivers like the mighty Mississippi and reservoirs created by man-made dams and levees. CWA covers ponds, and navigable waters, and sets standards for sewer treatment plants and surface waters.

The Clean Water Act came about as a major restructuring of the 1948 Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPC). Exhaustive amendments created a funding source for the construction of sewage treatment plants and established EPA authority to implement a permit program for discharging any pollutant into navigable waters from a point-source. Further amendments in 1987 eliminated construction grants, while establishing regulations that solidified state-federal relationships, such as the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, which empowered states to proactively manage water quality within their borders. Environmental protection laws and clean water regulations aim to protect humans, animals and aquatic life with short-term and long-term solutions to prevent contamination from irresponsible human activity and natural-occurring hazards.

Finally, let's briefly discuss the Clean Air Act (CAA) enacted in 1970. Prior to 1970 there were few regulations governing air polluting emissions from buildings, cars, trains, airplanes and other stationary and mobile sources. CAA gave the EPA authority to establish nationwide standards to regulate hazardous air pollutants, and to direct states to implement plans to appropriately mitigate air pollution by monitoring industrial activity and creating standards to reduce risks to public health and wellness. Amendments in 1977 and 1990 revised achievement goals because many states could not meet the rigorous requirements by the originate 1975 deadlines.

Environmental protection regulations and air quality laws govern residential wood burning stoves, hydronic heaters and forced-air furnaces used primarily for heat. Some states enacted more stringent laws than the EPA. For example, in 2016, passed ordinances that prohibit new construction buildings from installing any wood-burning appliance, even one approved by the EPA are “air-friendly.”

Every state has unique environmental protection regulations. As a real estate professional, it is your job to make sure you know about local, state and federal laws that regulate air and water quality. And, you should take the time to dig into the history of each building or piece of land you plan to list. A well-informed real estate agent becomes a proactive advocate for every client.

Key Terms

6.7 Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act

Transcript

Federal law applies to interstate transactions where a party in one state sells property to someone in another state. Coordinating these real estate transactions requires agents to follow regulations governed by the secretary of the United States Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) through the Office of Interstate Land Sales Regulation.

The set of rules that applies to these special arrangements is called the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act of 1968. Also known as ILSFDA or ILSA, the Act was passed by Congress as a tool to protect consumers from fraud stemming from the lease or sale of land across state lines. Anti-fraud provisions aim to protect buyers from getting stuck with property that turns out not to be as marketed. Most US buyers realize there isn't any ocean-front property in Arizona, but developers and real estate investors work with buyers and sellers in every state and every country around the globe. It is impossible to intimately know every street corner and country lane in every city, state, territory or foreign country.

Before we discuss some of the main requirements under the ILSFDA, we need to clarify a few terms in the HUD lexicon. First, interstate provisions don't just cover real estate contracts between buyers and sellers in different US states. The federal regulations apply to any offer to sell real estate located within incorporated and unincorporated boundaries of municipalities, counties, states, and foreign countries where consumer transactions are not sufficiently covered under State jurisdiction.

Keep these definitions in mind as you listen to this lesson on full disclosure regulations.

Lot:

Even though the Act's name seems to imply these regulations govern only land, that doesn't mean HUD only monitors sales transactions of unimproved acreage or tracts. HUD uses the word “lot” to describe any undivided interest in vacant portions of land offered for purchase, and land with structures – as long as the property for sale includes “exclusive use rights.” For example, condos, occupancy-ready homes, units in a subdivision and unimproved land are all “lots” as far as HUD regulators are concerned.

Sales:

HUD uses “sale” to describe any “obligation or arrangement” for consideration to buy or lease a “lot.” So, if you decide to read through the ACT, remember that “seller,” could also mean “lessor.”

Subdivision:

Describes a land section, whether already divided or as part of a plan to be divided in the future, for sale (or lease) as part of a shared promotional plan.

Now, let's look at some of the requirements for developers.

Congress passed the Act in response to growing concerns over fraudulent and deceptive marketing practices in the United States. Developers were pre-selling subdivision lots, or taking substantial deposits with a promise to begin development soon, and then delaying projects for many years. To prevent this consumer abuse, Congress established regulations that require subdivision registration with the appropriate government agency, and mandate contract cancellation options (rescission). Developers are also required to provide certain disclosures to the government and potential buyers.

Here are the main requirements.

Number One: Registration & Reporting

To ensure that consumers receive all appropriate information before signing a contract, ILSA requires some subdivision developers to register complete plans with federal regulators, and provide certain disclosures to prospective buyers. In 2011, changes to ISLA regulations J, K and L, mandated both Subdivision Developers and Condominium Developers with at least one hundred nonexempt lots/units register development plans, and provide all potential buyers with a comprehensive property report prior to contract signing.

Number Two: Informing Potential Buyers

Developers must provide certain information to prospective buyers before signing contracts. For example, in addition to giving buyers a copy of the right to cancel contract policy, developers must inform purchasers of the risks associated with buying lots. They also must deliver names and contact information for utility providers to allow verification of services and costs available, and provide a detailed list of all liens and encumbrances on the lot (or lots).

Number Three: Disclosing Progress Via Comprehensive Property Reports

We mentioned this report previously, but real estate agents and brokers sometimes get caught in the middle, between buyers and sellers, especially if full disclosure reports aren't accurate and up-to-date, so we are going to list some of the most important details included in this report. This report is intended to be very detailed in order to give buyers all the information they need to make an informed purchasing decision.

The report includes, but is not limited to, information on the following items related to each unit or lot:

- Construction of roadways, including the start date, expected completion date, percentage of project completion, road surface and units – such as miles or sections – distance traveled over paved and unpaved roads, and the population in nearby communities.

- Utility services, broken down by service, such as water, gas, telephone, electric, sewer, trash removal, etc. Information includes the provider’s name and contact information, along with the construction starting date, percentage of construction completed, expected date of completion, and date for services. This section also includes estimates for additional fees beyond the purchase price associated with connecting to utility service and dues for common area.

- Restrictions and association details include information about property owners associations, fees and covenants.

- Relevant documents pursuant to a pending sale may include zoning regulations, plats, surveys, environmental impact statements and permits.

- Statements on climate and subdivision characteristics include flood plain and soil erosion data, if applicable, drainage plans, environmental hazards specific to the location, occupancy restrictions, and nuisance ordinances or known issues.

- Additional notices may include resale or exchange programs, special situations particular to foreign transactions and violations and current litigation.

Depending on when developers sell lots, and whether homes, condos or other residential structures are on the property, other information may be included. Also with an address and phone number to reach federal regulators to file a complaint or confirm information in the report, every comprehensive property report should include the developer's name, address and other contact information, the name of the subdivision, complete location information (including county, state and country), selling agent's name, and the number of lots and the number of acres in the subdivision.

One final thought before we move away from the requirements. Although developers are required to register and submit reports, maps and plans for subdivision development, the federal government does not certify reports to buyers as accurate or complete. There are substantial financial penalties, and possible jail terms, if developers or anyone knowingly makes false statements on interstate sales disclosure forms. It behooves real estate agents to advise investors and private real estate clients to verify the information and to thoroughly read the rescission options before signing a purchase contract.

Now let's move on to a discussion about exceptions and exemptions.

Federal regulations provide three types of exceptions – full statutory and partial statutory exemptions for subdivision oversight and regulatory exemptions which permit exceptions for individual lots.

Let’s look briefly at a few exemptions.

Fewer than twenty-five lots exception. Small subdivisions with fewer than twenty-five lots are generally eligible for full statutory exemption. However, even subdivisions with more than twenty-five lots may be able to qualify if fewer than twenty-five lots are offered for sale because some lots – such as designated green spaces and parks – are offered for sale or lease under the common promotional plan.

Improved lots – land with a ready-for-occupancy residential structure – are eligible for full exemption status, providing construction can be completed within twenty-four months after the sales contract is executed. In this case, ready-for-occupancy means utilities are connected and the residence is fully habitable. Being obligated to complete one residential improvement does not obligate a developer to complete all buildings within a subdivision. Developers may opt to implement a staged development plan that allows full development to extend many years.

Business to Business Transactions

Sales to builders who purchase lots specifically for the purpose of building residential structures or for resale to a person or persons who plan to build residential housing are exempt from Federal regulations. However, selling or leasing land to an individual who plans to build his own home is not eligible for exemption status under this section of ISLA.

Zoned/Restricted Real Estate Transactions

Industrial and commercially zoned land is exempt from the Act, provided that certain conditions are met. Local authorities must approve access via a public roadway to at least one edge of the legal boundary of the subdivision. In addition to the access, the purchaser or lessee must be a legally organized business entity, before recording the deed or executing a lease. Finally, the purchaser must attest in writing that the property will be used solely for commercial or industrial activities of the entity, or provide evidence that there is a legal binding agreement in place to sell or lease to a business engaged in commercial business activities.

The Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act is complex, and changes from time to time to ensure consumers have protection against fraud and abuse when dealing with out-of-state developers and land investors. Sometimes other federal agency rules and guidelines overlap or directly and indirectly impact ISLA. You may see regulations from the Consumer Finance Protection Agency drive changes to the Act, as well as EPA rules that dictate certain subdivision master plans. To best serve your clients, stay informed about pending legislation and amendments that govern sales and marketing activities within your state and beyond the borders.

Remember, it is possible to be caught in the middle if you aren't fully aware of the basic requirements and exemptions of the Act. Protecting your professional reputation and personal financial assets starts with educating yourself and your clients about local, state and federal real estate laws.

Key Terms

COPYRIGHTED CONTENT:

This content is owned by Real Estate U Online LLC. Commercial reproduction, distribution or transmission of any part or parts of this content or any information contained therein by any means whatsoever without the prior written permission of the Real Estate U Online LLC is not permitted.

RealEstateU® is a registered trademark owned exclusively by Real Estate U Online LLC in the United States and other jurisdictions.